Old English, Young Language

English has its origins in the Germanic tribes that conquered Britain in the fifth century CE. Old English is the collective name given to the regional dialects spoken by these tribes from their arrival through the early 1100s. It is the language of Beowulf and most speakers of modern English would find it largely unreadable without some training. The first lines of Beowulf, for example, are:

Hwæt, we Gar-Dena in gear-dagum

þeod-cyninga þrym gefrunon,

hu ða æþelingas ellen fremedon

(which has been translated by R. D. Fulk as “Yes, we have heard of the greatness of the Spear-Danes’ high kings in days long past, how those nobles practiced bravery”).

In 1066 at the Battle of Hastings, William of Normandy earned his epithet “the Conqueror” by defeating the forces of England's King Harold. The Norman Conquest brought with it an influx of the French language from the new rulers. This combined with other factors to transform the English language over many decades, ultimately yielding Middle English, the language we associate with Chaucer.

_____________________________________________________________________________

How Language (Sometimes) Survives

The story of how these two manuscript leaves containing different Old English texts came to reside at KU offers an example of one of the ways that early manuscripts are “lost” and then recovered (or in this particular case, uncovered). In 1957, the library bought a copy of a 1636 edition of the English translation of John Barclay’s Argenis from Pearson’s Book Rooms in Cambridge. Once the volume arrived at KU, librarians noticed that the seventeenth-century calf of its binding was separating from the pasteboard, revealing an Old English manuscript leaf. Another Old English leaf from a different text was uncovered in the opposite board. One leaf is a fragment from “The Legend of the Holy Cross before Christ,” copied circa 1000-1050 (right), and the other is a fragment of a homily by Ælfric, Abbot of Eynsham, copied circa 1050-1099 (left). Both leaves are glossed in Latin by the “Tremulous Hand of Worcester,” a thirteenth-century annotator of Old English texts known for distinctively shaky penmanship.

Scholar Bertram Colgrave and former KU manuscripts librarian Ann Hyde traced the leaves to manuscripts once held by Matthew Parker (1504-1575), Archbishop of Canterbury and a scholar and collector of Old English manuscripts. The leaves were likely removed by Parker himself and, eventually, ended up in a binder’s scrap pile to be re-used in the mid-1600s in the binding of our copy of Barclay His Argenis. Look closely at the piece of the original leather binding on display, and you will see where ink has transferred from the Old English leaf once pasted to it.

1. Fragment of “The Legend of the Holy Cross before Christ.” Worcester (?), England, circa 1000-1050, with 13th-century annotations by the Tremulous Hand of Worcester. Call #: MS Pryce C2:1

2a. Ælfric, Abbot of Eynsham. Fragment of “Sermo in natale unius confessoris.” Worcester (?), England, circa 1050-1099, with 13th-century annotations by the Tremulous Hand of Worcester. Call #: MS Pryce C2:2

2b. Binding leather with transfer of ink from the Old English leaf containing a fragment of Ælfric's “Sermo in natale unius confessoris." 1636 or later. Call #: MS Pryce C2:2:leather

_____________________________________________________________________________

The two Old English leaves above (MS Pryce C2:1 and MS Pryce C2:2) were found in the original binding of this 1636 printed book, where they served to reinforce its front and back boards. It was a common practice for binders to use printed and manuscript "waste" in their bindings.

3. John Barclay. Barclay His Argenis. Or, the Loves of Polyarchus & Argenis. Translated into English by Kingsmill Long. London: Printed for Henry Seile, 1636. Call # C34

_____________________________________________________________________________

Gegrindswile: KU's Old English Word

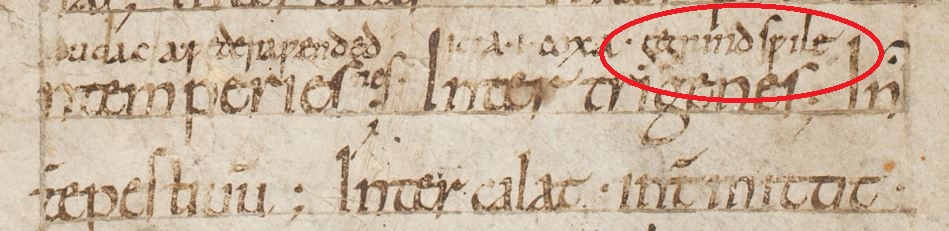

This rather weathered-looking leaf contains perhaps the sole surviving instance of an Old English word: gegrindswile. Like many words of Germanic origin, gegrindswile is a compound. Its two parts – gegrind and swile – survive in other texts, but this leaf is the only instance recorded in the Dictionary of Old English Corpus of the two combined. Together they form a single word meaning “a swelling caused by friction, a chafing or galling (of the skin).”

The leaf on which gegrindswile appears is from an early eleventh-century glossary giving brief definitions of difficult Latin words. Most of the leaf’s glosses are also in Latin, but several are in Old English, including gegrindswile, which glosses the Latin word intertrigenes. You will notice that gegrindswile contains a letter that does not survive as such in modern English: “ƿ.” This is the runic letter “wynn,” which represents our modern “w” sound. KU holds only a single leaf (two pages) from the glossary; however, the British Library holds a seemingly related manuscript. Its collections include a Latin glossary for the letters A-F, also with Old English glosses, written in the same scribal hand as KU’s leaf.

4. A Leaf from a Latin glossary with Old English glosses, covering the words interkalares to istingum. Worcester (?), West Midlands, England, circa 990 - 1010. Call #: MS Pryce P2A:1

_____________________________________________________________________________

This incomplete manuscript roll was likely created in England around 1240-1260 CE, nearly two hundred years after the Norman Conquest. It offers a history of the kings of Britain, from the Roman Emperor Severus to Uther Pendragon, father of the mythic King Arthur. It therefore covers a period of time (circa 200-475 CE) before and leading up to the emergence of the English language. The roll draws on chronicles of English history, including in the leftmost column that of Geoffrey of Monmouth, and like Monmouth’s text is composed in Latin. The two dragons on the right may represent the Prophecy of Merlin, which tells of a battle between a white dragon (the Saxons) and a red dragon (the Britons). The scroll, in both its historical content and in its thirteenth-century date of composition, is an artifact that embodies the multiple and changing cultures and languages of Britain.

5. Chronica regum Britanniae [History of the Kings of Britain]. England, circa 1240-1260. Call #: MS Pryce J1

_____________________________________________________________________________

During the English Reformation, figures such Matthew Parker (1504–1575), Archbishop of Canterbury, spurred a new interest in Old English manuscripts. Motivating Parker was the need to establish a historical precedent for the tradition of an English Church independent from Rome. However, in order for Old English works to be printed, disseminated, and studied, new fonts of type were needed to represent Old English characters such as eth (ð), thorn (Þ), and wynn (ƿ), as well as letters whose appearance had changed significantly. John Day created the first Anglo-Saxon type in 1566 and used it to print A Testimonie of Antiquitie (1566), shown here in its second edition of the same year. The volume is a part of Spencer’s Clubb Collection, a typographical collection comprising books that use Old English type.

The passage on display addresses the issue of transubstantiation, a point of difference between Protestant and Catholic doctrine. As the annotations suggest, it was a topic of particular interest to an early reader of this copy.

6. Ælfric, Abbot of Eynsham. A Testimonie of Antiquitie, Shewing the Auncient Fayth in the Church of England Touching the Sacrament of the Body and Bloude of the Lord Here Publikely Preached, and also Receaued in the Saxons Tyme, aboue 600. Yeares Agoe. London: John Day, [1566?]. Call #: Clubb A1566.1

_____________________________________________________________________________

Dubbed the “Saxon Nymph,” Elizabeth Elstob (1683–1756) was an early scholar of Old English. At a time when women had limited access to education, Elstob learned Old English from her brother, an Oxford fellow, and became part of a circle of Anglo-Saxon scholars. Her first major Old English publication was this edition of Ælfric’s An English-Saxon Homily on the Birth-Day of St. Gregory (1709). The historiated initial that begins the translation captures her likeness. In the volume’s preface, Elstob defends both women’s pursuit of education and the value of studying the history and language of the Anglo-Saxons, a subject that some contemporaries viewed as barbarous in comparison to the languages and history of Continental Europe. Elstob also authored the first Old English textbook written in English rather than Latin, The Rudiments of Grammar for the English-Saxon Tongue (1715).

7. Ælfric, Abbot of Eynsham; Elizabeth Elstob, translator. An English-Saxon Homily on the Birth-Day of St. Gregory. London: W. Bowyer, 1709. Call #: Clubb C1709.2

_____________________________________________________________________________

Elizabeth Elstob created the manuscript that is on display. It is her quasi-facsimile transcription of the Latin canticle "Audite caeli quae loquor," with later twelfth-century Old English glosses, from a psalter held by Salisbury Cathedral. She made the transcription as a gift to her brother’s patron, William Nicholson, Bishop of Carlisle, an antiquarian scholar. In the book’s title inscription, Elstob wrote her name in Old English runes, as the Anglo-Saxon poet Cynewulf did in signing his works. Runes are an early angular alphabet used by a variety of Germanic languages; Old English runes survive primarily in carved inscriptions and in records of runic alphabets.

(Elizabeth Elstob)

8. Transcription by Elizabeth Elstob of the Canticle "Audite caeli quae loquor," from the tenth-century Salisbury Psalter. Oxford, 1709. Call#: MS B93 item 1